by Dr. Joanna Sliwa

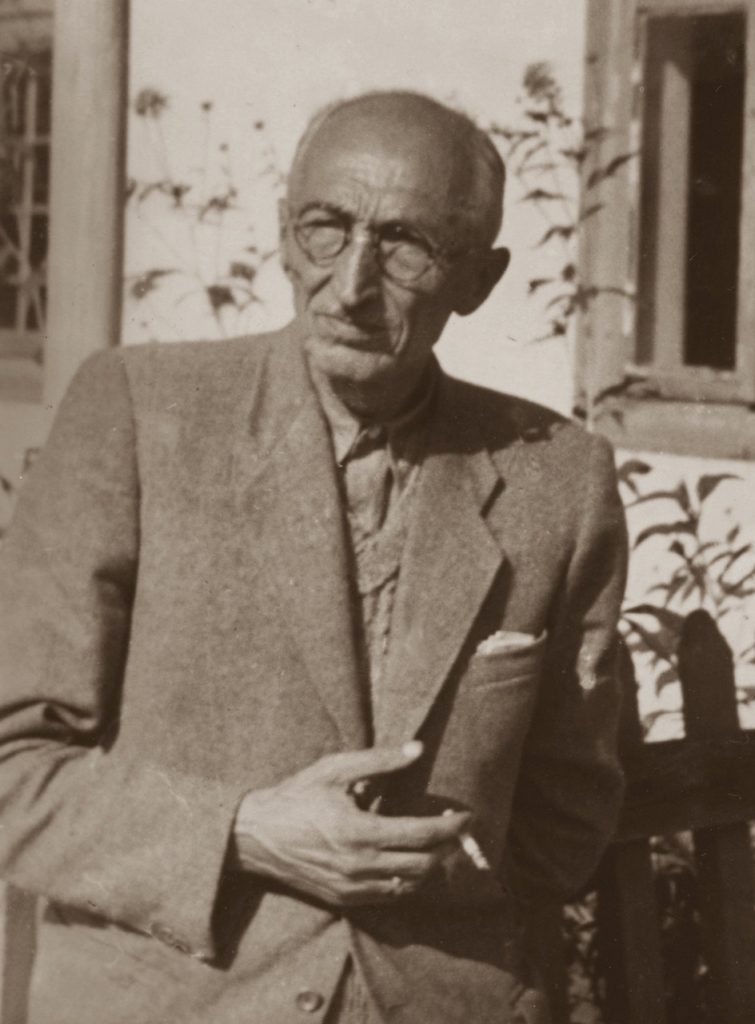

Jan and Melania Mikulski lived in Wola Duża, a village in the Lublin region in eastern Poland. They had three children: Jadwiga, Danuta and Jerzy. Jan was a forest ranger, and the family lived a relatively quiet life, away from the German authorities stationed in the nearest town of Biłgoraj. However, the Mikulskis’ lives changed suddenly in 1942.

Because of its location near the Soviet-Polish border, Biłgoraj had been occupied thrice in 1939 – by the Germans for a few days in September, then by the Soviets in accordance with the German-Soviet pact, and again by the Germans in November. Before the war, Jews (over 4,000 residents) constituted approximately half of the town’s population. Over 1,000 Jews managed to flee with the retreating Soviet army. Those who remained were subject to Nazi anti-Jewish policies, such as the compulsory wearing of the Star of David armband to mark Jews for swift identification and persecution. The German authorities ordered the confinement of nearly 3,000 Jews in specific areas of Biłgoraj. Expulsions of Jews from Biłgoraj and transfers of Jews to the town from elsewhere followed. In August 1942, the German authorities deported over 1,000 Jews to the Bełżec killing center.

Danuta Mikulska was 12 years old at the time. In an oral history recorded many years after the events, she recalled that several Jews slipped from Biłgoraj to meet with Danuta’s father and try to arrange for hiding their loved ones for payment. He refused not only because of the involvement of money, but also fearing the safety of his wife and their three children. Hiding Jews was punishable by death. “And then people came, and we kept them without taking money,” Danuta stated.

Photo: Yad Vashem

In the first days of November 1942, a German police battalion, joined by Lithuanian and Ukrainian auxiliaries, conducted a major deportation action of Jews from Biłgoraj and a few surrounding localities. They forced Jews to march on foot to a nearby station where they would be loaded onto cattle cars and sent to Bełżec. Danuta recalled those terrible days because she was staying overnight with her relatives in Biłgoraj after visiting the cemetery on All Saints Day (November 1). When she returned home, Danuta witnessed the columns of Jews being led on the road near the house. From behind a curtain, so as not to risk being seen by any German, Jan said to his family members: “You will see and remember until the end of your lives what people can do to other people.”

Ten-year-old Ryfka Wajnberg managed to slip from the march and reached the Mikulski home. Her parents had known the Mikulskis. Danuta heard the girl’s cries, “I don’t want to die! I’m scared! Save me!” The problem was that the Jewish girl arrived at the household when Danuta’s father was meeting with a group of Polish men. All of them saw the Jewish escapee. A German order specified that if found, all Jews had to be brought to the German authorities. Jan Mikulski thought quickly and used all the cunning and courage that he could muster at that moment. To implicate the Polish men in saving the Jewish girl, he offered, to the other men’s agreement, to leave the girl in the forest where she would have to fend for herself. In contrast to other men who displayed no intention to help the child, Mikulski knew that he could not leave the girl because she was completely helpless. He also knew that there would be no one else willing to hide her. So, he decided to shelter Ryfka. For a few days, his neighbors, the Barański family, kept the girl, and then Mikulski took Ryfka to his house.

Since summer 1942, the family had been already harboring another Jewish girl, an orphan from before the war, Malka Wakslicht. Ryfka Wajnberg’s mother pleaded with Melania Mikulski to take in the girl, who until then had served as household help in the Wajnbergs’ home. Jan Mikulski, who knew the forest very well, took Malka to a hideout deep in the forest. Jan’s two daughters brought the girl food and whatever they could find to keep her warm. Once Ryfka arrived, the two Jewish girls were hidden in a bunker inside the stable. They were afraid of all the sounds, the darkness, and that someone would find them. Mikulski instructed the girls to hide under a trough in case of emergency. Another protection measure was a dog tied in front of the entrance to the stable to deter strangers.

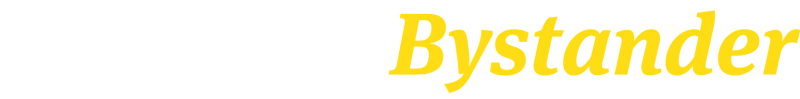

Soon after Ryfka had arrived in the Mikulski’s house in fall 1942, three more Jews reached the house – Bencjon Rozenbaum, his nephew Chaim Rozenbaum and his niece Perla Frajberg (later Kenig). Jan Mikulski knew Bencjon because Bencjon had worked as a wood sorter before the war. The three family members, too, hid in a bunker on the Mikulskis’ property.

For some time, mainly for safety reasons, the three older Jews were unaware that two Jewish girls were hidden in another bunker on the property. Hunts for Jews in hiding proceeded after the liquidation of the Biłgoraj ghetto in January 1943. The Mikulskis even considered finding new locations for the Jews to save some lives in case others (including the Mikulskis) were informed on to the authorities. However, as Danuta recalled, neither the Mikulskis nor the Jews had the money and valuables to offer to other aid givers, and it was common knowledge that some local peasants took the money and murdered the Jews. The Jewish people were thus the safest in Mikulskis’ care. The Mikulskis and their rescuees dug out a bunker in the stable for all the Jews to hide.

Danuta recalled that the five Jews remained under her family’s protection for one year and ten months. The non-Jewish family shared everything they had with the people under their care. They did this while enduring excruciating fear of being denounced by their neighbors. And yet, the Mikulskis never once thought about telling the Jews to leave. Danuta recalled that the fear of denunciation, a German raid, and death were overwhelming for her mother. It was she, Melania, who had to stay behind while her husband left for work. The Mikulskis’ fears peaked when German soldiers commissioned space in the family’s home for a few days in summer 1943. The Mikulskis prepared for the worst.

Danuta recalled that it was her father’s polite demeanor and fluency in the German language that assuaged the Germans stationed in their home. The German officers actually saved the Mikulski family from a German-incited resettlement action of the Polish population. Thus, the Mikulskis, and, unknowingly to the Germans, the five Jews continued to live in Wola Duża.

In addition to sheltering Jews, Danuta’s father also provided ad hoc assistance to others. Danuta stated that her father was giving food to a Jewish father and son. The two hid in a bunker in the village of Ratwica, 6 miles away. The father was killed after the war. It was not uncommon for local Poles to not only harass, but murder Jewish survivors. The man’s son emigrated to the United States.

After the war, Chaim Rozenbaum joined the Polish Army and was killed in northern Poland. Bencjon Rozenbaum immigrated to Israel with Perla Freiberg (later Kenig). Bencjon remarried but did not have more children (his wife and children were killed during the Holocaust). Perla had two sons. She passed away in 2002. Jan Mikulski found out about a Jewish committee in Lublin, which had been liberated in summer 1944. He placed Ryfka Wajnberg and Malka Wakslicht in a Jewish orphanage. The girls later settled in the United States. Ryfka (later Goldshmidt) had one son. She passed away in 2011. Malka’s whereabouts could not be established.

According to newest research, those five Jews were among the 2 percent of all the Jews (274 people) in the Biłgoraj county who survived the German occupation. About 1,500 Jews, including those at the Mikulskis’ home, hid in the Biłgoraj area. Those who did not survive, were found by the Germans and killed, were murdered by their Polish aid givers, or were killed by Poles during hunts for Jews in hiding.

Danuta was a child during the Holocaust. The German persecution of the Jews of Biłgoraj shocked her. Despite her young age, she exhibited great maturity, exercised agency, and risked her life to help Jews, both younger and older than her. She was a trusted confidant of her family’s secret. Danuta brought food to the Jewish girls while they stayed in a hideout in the forest. She also cared for them and the three other Jews while they hid in a bunker in the barn. Her family’s prewar connections to Jewish inhabitants of Biłgoraj, as well as the location of the Mikulskis’ house near the forest and on the road to the deportation station, made the Mikulskis a key point of contact for Jews seeking help and shelter. These Jews, as well as the father and son who received ad hoc assistance, knew that the Mikulskis were decent people who were guided by moral principles to help another human being. In the course of their rescue activities, the Mikulskis were faced with tremendous fear and knowingly risked their lives. Although they themselves did not have much, they shared everything with the people under their care.