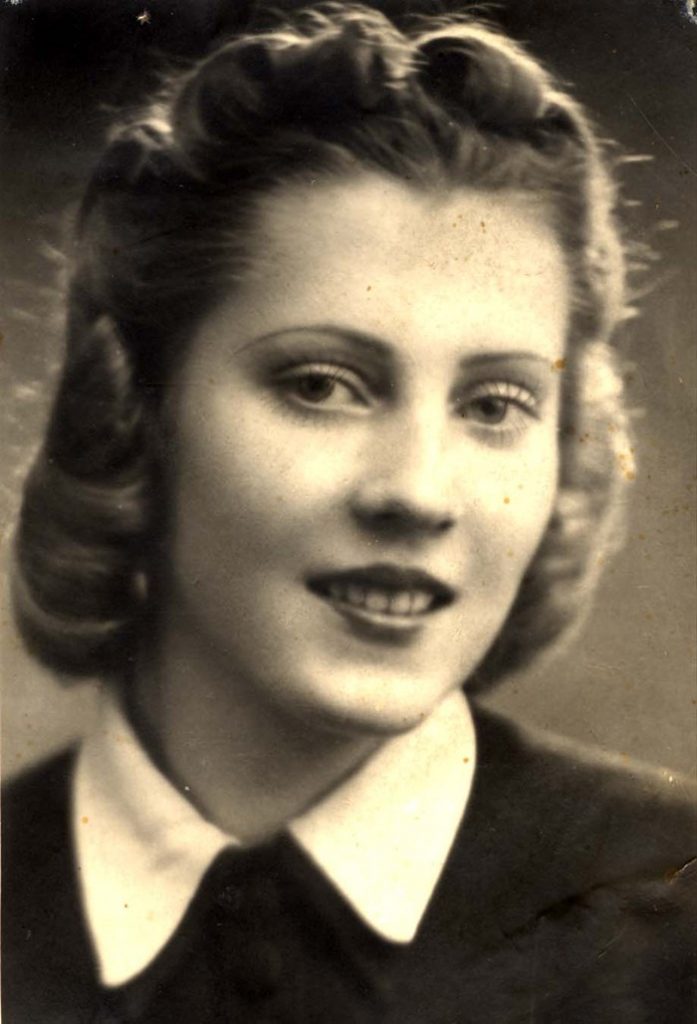

In 1939, Irena Gut (later Irene Gut Opdyke), was thrust into the war effort as a 17-year old nursing student in Radom, Poland. She was drafted to provide medical care to retreating Polish soldiers and accompanied them to Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania. There, Gut learned that the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had carved out Poland between themselves. Without anywhere else to go, she followed the army unit to Lwów (today: Lviv, Ukraine). There, Gut was raped by Russian soldiers. She was then transported to a Russian hospital where she fled another sexual assault.

Gut then found work at an infirmary and assumed the identity of a Jewish woman to avoid being discovered as a fugitive. In 1941, she mustered the courage to register to reunite with her family in Poland, under false identity as a person of German descent. With her knowledge of German, her surname and her Germanic physical features, she managed to deceive the German authorities.

Back in Radom, Gut was rounded up and taken slave to toil in a local munitions factory. Again, her name and fluency in German saved her – the major who had selected her for the job now delegated her to work as a domestic for a German official in his villa. With the windows of his villa overlooking the ghetto, she witnessed the persecution of the Jewish residents, including a mass shooting. This shocked Gut but with access to food in the German’s kitchen, Gut decided to take the risk and not only smuggle some outside, but also leave it under the ghetto fence for the Jews to find. I knew it was a drop in the ocean, but I could not do nothing, she recalled in her memoir written after the war.

Irene was given a job working in a kitchen by a German major – she was to serve food to As the German war effort turned the east, the munitions factory, and its staff, including Gut, moved to Ternopol in August 1942. Jewish workers from a local labor camp were brought in daily to work in the laundry, which fell under Gut’s oversight, and she became close to them. One night, while serving dinner to the Germans, she overheard their discussions to wipe out the Ternopol ghetto and ship all the remaining Jews from that area to camps. Gut used her charm, young age, and feigned disinterest to her advantage – she was collecting information to help her Jewish friends make decisions about flight from the ghetto and avoid round-ups. She also garnered all her courage to approach a feared Nazi to obtain permission to enter the ghetto and smuggled out one worker whose family had been taken in an action. She soon smuggled six Jewish workers to hide in a nearby forest. More than that, she continued to provide them with necessities and information. I did not become a resistance fighter, a smuggler of Jews, a defier of the SS and the Nazis, all at once. One’s first steps are always small: I had begun by hiding food under a fence, Gut reflected on the process of becoming a rescuer in her memoir. She was aware of the risks and accepted them.

When Gut was transferred to serve at the villa of a German major whom she had known from Radom, she saw this as an opportunity – she smuggled all 12 Jewish friends into the basement of the villa without the knowledge of the major. She did this with the explicit knowledge that anyone caught helping Jews would be put to death immediately. Among those hidden were Lazar and Ida Haller who were expecting a baby; they knew it would cry and give them away…thus risking all of their lives including Irene’s. They offered to give up the child, but Irene refused.

There were several close calls at the villa – including the day when a Polish couple and their two children, and a Jewish couple and their young child were all hanged. Everyone was forced to watch to see what happened when one helped Jews. Irene was so shaken by this that when she came home, she forgot to lock the door and when the major came home early, he caught the Jews upstairs. The major, then in his 60s, forced 19-year-old Irene into an ongoing sexual relationship in exchange for keeping quiet about the family she had been hiding.

This continued for several months until finally it was clear the Germans were losing the war. They had a radio, so they knew the Russians were coming. They all fled to the forest as the Russians came; they were freed. In May 1944, the baby – Roman Haller – was born.

Years later in a television broadcast, Holocaust survivor Roman Haller, born at the end of the war, was quoted saying, “Irene for me is like a mother, maybe even more, like someone who has given birth to me. Irene saved my life, and not only my life, the lives of my parents.”