by Dr. Joanna Sliwa

Ethnic Germans Hiding Jewish Families in German-Occupied Poland

Photo: Kean University

Clara Schwarz was 12 years old in 1939 when World War II broke out and the Soviet Union annexed her Polish hometown of Żółkiew (today: Zhovkva, Ukraine). In summer 1941, the town was occupied by Germany. There is terror and panic in our city. The Jews are building bunkers of all kinds: underground, double walls, anywhere they could find a spot to hide. Others are looking for help from the gentiles, Clara described the situation in her diary that many years later she turned into a memoir. She spoke about her experiences in oral histories. Clara’s parents and sister, as well as two other families – the three-member Melman and three-member Patrontasch families – decided to join forces and build a bunker in the cellar of the Melmans’ house because it was the biggest of the three houses.

In November 1942, the three families slipped into the hiding place when deportations of Jews to the Bełżec killing center intensified and when the German authorities ordered all Jews into the ghetto in Żółkiew. A local couple, Julia and Walenty Beck, agreed to move into the Melmans’ house and protect the Jewish families. Julia had a prior connection to the Schwarzes – she had worked in their home. Clara knew that she could trust Julia. However, she was concerned about Julia’s husband. Clara asked in her memoir, Could we risk putting our lives in the hands of a man who was known for a vicious tongue, his anti-Semitism, for his affection for drink and failed businesses? Walenty Beck’s example shows that there was no one profile of a rescuer during the Holocaust.

The Becks and their daughter Aleksandra registered as ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche). This designation gave them better treatment and access to local German authorities, and, thus, to information. Their status could also veer off suspicion that they could be harboring Jews. In the 20 months until liberation in summer 1944, the Becks had sheltered 18 Jews in the bunker, of whom 17 survived (Clara’s sister, Mania, was denounced by a Pole when she exited the hiding place). The Becks and the Jewish families in hiding faced many dangerous situations that could have exposed them – from visits of the Germans in the house, a fire that erupted in a neighboring building and endangered the lives of the Jews in the bunker, rumors that the Becks were helping Jewish families, and the death penalty that was imposed on anyone discovered to be assisting Jews in any way. The Jews in hiding and their protectors also faced potentially perilous situations when additional Jews, including Clara’s two young cousins who had fled from the ghetto, appeared in the Beck’s house. Then too, the relations between the rescuers and rescuees strained over time because of the constant fear, clash of personalities, confined space, lack of privacy, and power struggles. Despite the challenges, the Becks continued to shelter the Jews.

Clara was one of 50 Jewish survivors in Żółkiew out of the prewar Jewish population of about 5,000. As in other areas in German-occupied Poland, and throughout Europe, rescue was the exception. The diary that Clara had written in hiding provided evidence to the Russian authorities that liberated her town that the Becks were not German collaborators, but rather they were rescuers of Jews. Clara maintained contact with her wartime protectors and their descendants all her life. In her memoir she stated, Since I was a child, I’d been told the stories about the 36 righteous for whose sake God didn’t destroy the universe. I liked to think that Mr. and Mrs. Beck were two of them. Walenty, Julia, and Aleksandra Beck were recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations in 1983.

After the war, Clara emigrated to Israel, and eventually settled in the United States. She married another Holocaust survivor, Sol Kramer. Together they had two sons. Before she passed away in 2018, Clara Kramer was a founding member of the Holocaust Resource Center of Kean University in New Jersey and remained an active supporter of it. She spoke widely about her experiences during the Holocaust, always celebrating the courageous choices and actions of her rescuers, the Becks. The next generations carry the torch of remembering and honoring the Righteous people who rescued Clara, her immediate family, relatives, and neighbors.

A Catholic Priest and a Rescue Network in Belgium

Hena Kohn was barely a year old in 1930 when she and her parents emigrated from Łódź in Poland to Brussels, Belgium. In May 1940, the family’s situation changed radically with the invasion of the German army. The Kohns, as did many Jews from Belgium, fled toward France. Once they learned the fighting was over, the Kohns returned to Brussels. Anti-Jewish laws in Belgium intensified. These included the order for Jews to wear a marking (the yellow star) and perform forced labor. Deportations were imminent.

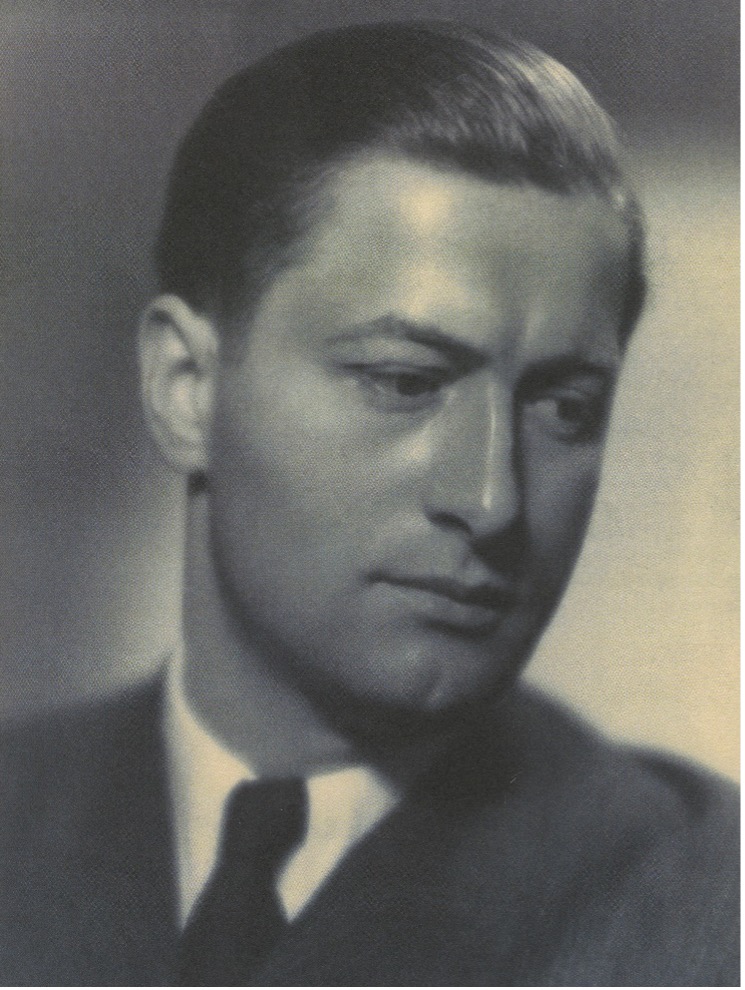

In summer 1942, to protect them from the growing danger, a Red Cross worker, Ms. Van der Stiekelen, agreed to hide Hena and her younger sister Paula in her villa for a few days. The girls’ parents came to bid them farewell before the girls’ journey to a Red Cross summer camp in the Ardennes. That was the last time that Hena and Paula saw their parents, whom the German authorities deported to Auschwitz. Unable to return to Brussels after the summer vacation, the Red Cross worker arranged with a Belgian resistance group to help her hide the two girls. Edouard Robert, a Catholic priest, was sent by the network to facilitate the rescue.

The Kohn sisters were separated either for safety reasons or because it was difficult to find an individual or a family willing to shelter more than one Jewish child. Hena was placed on a farm. The priest served as a liaison in the rescue operation and understood that living in a completely foreign environment was hard for a 12-year-old girl. He sometimes took her to his family in Bastogne to ease her life.

Photo: Yad Vashem

When it was no longer possible for Hena to remain with her aid givers, the priest was compelled to find a new location for Hena. He placed Hena in a boarding school run by a convent. Yet, life among the nuns, in a fully Catholic environment, with its pressures and expectations to adhere to Catholic practices, was onerous. The priest thus found another place for Hena, with Athanse and Maria Jacquemart in Neufchâteau, and later with his own mother, Alix Robert.

Edouard Robert used his connections and position as a clergy member to solicit people willing to take in Jewish children. The priest helped to shelter not only Hena and Paula Kohn, but also Hena’s uncle, Francois Shumiliver, and his son Marcel, and another cousin, Semmy Miller (later Jean Desmet). Robert also aided two other Jewish families. While Catholic values may have played a role, the priest was also motivated by the personal relationships that he forged with the Jews under his care. He, and the non-Jewish individuals and families that he recruited, faced constant fear of denunciation. The German authorities offered incentives to Belgians for identifying Jews in hiding and their aid givers.

After liberation, Hena returned to Brussels with her uncle and cousin. Although she was still a teenager when the war ended (she was 16 years old), she was quite independent and assumed care over her younger sister. Eventually, Hena emigrated to Israel where she married Azriel Gutwirth (later Evyatar). Hena provided a detailed account of her rescue in a Hebrew-language testimony recorded in 1997 for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive.

In 1999, Yad Vashem recognized Edouard Robert and his mother Alix Habay Robert, as well as Athanse Jacquemart and Maria Collard Jacquemart, and Athanase’s sister Marie Jacquemart as Righteous Among the Nations.

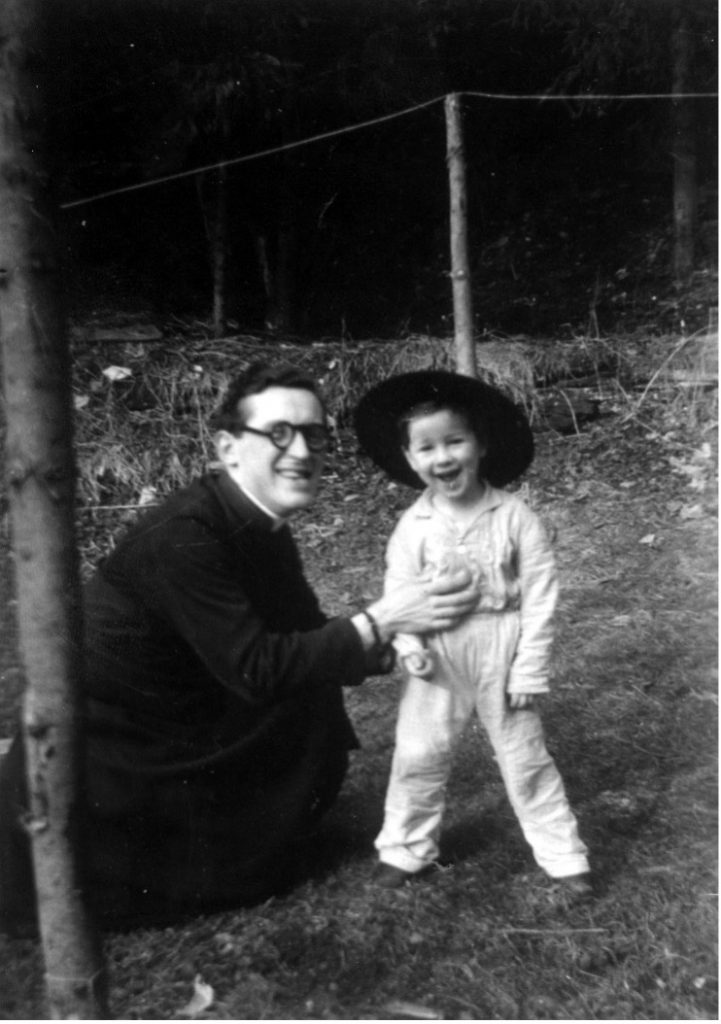

An El Salvadoran Diplomat Issuing Citizenship Papers

Diplomats stationed in Europe were obliged to adhere to their respective country’s immigration policies. Yet some, having witnessed the deteriorating situation of Jews in Germany and elsewhere, made the difficult decision to contravene the official policy. One such diplomat was José Arturo Castellanos from El Salvador. As a consul in Germany, he repeatedly petitioned his superiors to issue visas to Jewish refugees. To no avail. He made the difficult choice to no longer be a bystander upon his transfer to the neutral Switzerland in 1941.

The Geneva consulate of El Salvador, under Castellanos’s management, issued citizenship certificates to thousands of Jews in occupied Europe to protect them from deportation. Those Jews had no ties to El Salvador, including no knowledge of the Spanish language. And yet, such documents allotted their Jewish recipients some measure of protection from persecution because the German authorities still gave some weight to foreign governments and their subjects (even if they suspected that the documents were falsified). For example, Jews who held citizenship papers of neutral countries, of countries allied with Germany (to some extent and until a certain time), and of the Americas were sometimes spared from deportation actions in ghettos and were held in camps, such as Bergen-Belsen, where they served as pawns in exchange for Germans. Of course, not every intended recipient had the opportunity to use the documents. At times, the papers reached them too late despite every effort made to attempt to save the person.

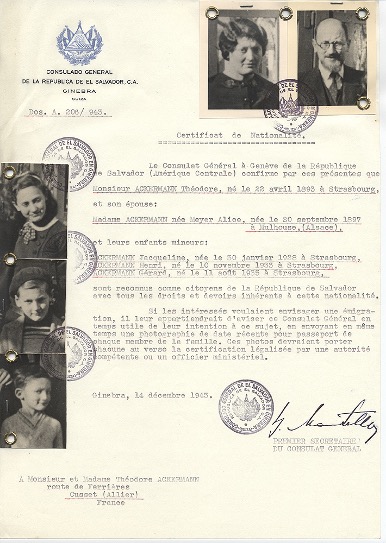

George Mandel-Mantello Photo: USHMM

Such a rescue operation was only possible thanks to a joint effort of Castellanos and George Mandel-Mantello, a Hungarian Jewish businessman who took on a Spanish-sounding version of his last name. Castellanos had known Mandel-Mantello prior to the outbreak of World War II and appointed him as his consulate’s First Secretary. In his official and clandestine roles, Mandel-Mantello began to provide documents to Jews claiming they were citizens of El Salvador in August 1942, as deportations of Jews to killing centers in German-occupied Poland accelerated. Mandel-Mantello relied on the joint efforts of Jewish organizations that supplied photographs of Jews and their personal information. A network composed of couriers distributed official copies of over 1,000 certificates of citizenship for free to Jews in German-occupied Europe.

With a new government in El Salvador in May 1944, the new president decided to join other western countries that were engaged in rescuing Jews in Hungary. In March 1944, Germany occupied Hungary, its former ally, and proceeded with ghettoization and deportation of Jews mainly to Auschwitz. It was then, with the shift in his own government, that Castellanos was granted permission to pursue his rescue activities. And it was at that point that this endeavor assumed the greatest need and carried the greatest weight. In fall 1944, the new fascist Hungarian government recognized the Swiss legation in Budapest as a proxy of El Salvador in Hungary. This allowed Mandel-Mantello to supply blank citizenship papers to the Swiss Consul there who then forwarded the papers to Jews, thereby saving them from deportation.

Castellanos and Mandel-Mantello worked alongside many individuals and groups to save Jewish lives all over German-occupied Europe. Thus, Mandel-Mantello engaged not only in resistance against Nazi anti-Jewish policy but also in rescue of other Jews. Jewish rescuers of other Jews are not formally recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. According to Yad Vashem, the criterium of risk, meaning endangering one’s life willingly for the sake of saving a Jew, distinguishes help provided by Jews from help provided by gentiles. Jews were slated for destruction on racial grounds, established by the Nazis, regardless of what they did. Although no official designation exists at Yad Vashem for Jewish rescuers, their histories are highlighted in many ways.

Castellanos was 50 years old when he assumed the role of a rescuer of Jews. His story shows us that it was possible for individuals of different ages, social and professional positions, and national belonging to engage in saving Jews. Some, such as Castellanos, made the decision to help Jews who were total strangers to him and, in doing so, to breach his country’s policy and risk charges of insubordination. This could have cost him not only his social and professional status, but also his freedom. His perseverance, and a shift in power, as well as the changing military situation, led Castellanos to win official permission to conduct his rescue activities. In 2010, Yad Vashem recognized José Arturo Castellanos as Righteous Among the Nations.

An Austrian Businessman Saving Jews in German-Occupied Poland

Julius Madritsch was in his early 30s when he arrived from Vienna, Austria, in Kraków in German-occupied Poland. As a businessman and textile expert, he managed factories that the German authorities had confiscated. When they gave him permission to set up a factory near the Kraków ghetto, Madritsch used this as an opportunity to assist his Jewish laborers. He recruited a fellow Austrian, Raimund Titsch, who was in his early 40s, as his factory manager to oversee the workers. The help that the factory managers extended to Jewish workers consisted of better food and more bearable conditions.

In addition to Kraków, Madritsch opened a factory in nearby Tarnów. There, too, he offered manageable working conditions, making this a coveted place to work for Jews from the Tarnów ghetto. Madritsch extended his activities on behalf of Jews by using a factory vehicle to smuggle food into the ghetto.

Kraków, 1942 Photo: USHMM

Realizing the scope and scale of Nazi persecution, Madritsch began to facilitate Jews’ rescue by connecting his workers with a German policeman, Oswald Bouska (Bousko/Bosko), who was willing to help. Bouska agreed not to keep a count of Jewish workers upon their entry to and from the Kraków ghetto and their place of work. This allowed some Jews to escape and to arrange hiding places for their loved ones by forging connections with Poles outside the ghetto. The building of Madritsch’s factory in Kraków served as a hiding place for Jews who evaded deportation during the final liquidation of the ghetto in March 1943. Some of the Jews managed to find Poles willing to hide them. Others were smuggled through a Polish-Jewish-Slovak rescue network across the Slovak border, to Hungary. Still others, without a place to go and a person to turn to, slipped into the nearby Plaszow camp (which until January 1944, when it became a concentration camp, had been a labor camp specifically for Jews).

Until September 1943, Madritsch had secured the German authorities’ permission for his workers to march daily from the camp to the factory in the former ghetto. This way, Jewish prisoners could leave the terror of the camp at least for some time. Once leaving the camp on a daily basis became forbidden, Madritsch established a workshop inside the Plaszow camp. Workers from both Kraków and Tarnów ghetto, in all about 2,000 Jews, labored in his plant. This was the largest slave labor compound in the camp. It was known among Plaszow prisoners as a hospitable place of work with its better food rations and a more humane treatment than in other slave labor assignments.

In fall 1944, the Red Army was approaching from the east and the German authorities, still determined to exploit Jews, began to evacuate the prisoners westward. Madritsch won permission to transfer fewer than 100 of his Jewish workers to the munition factory operated by Oskar Schindler. Schindler evacuated his Jewish workers from Kraków to Brünnlitz, in the Czech lands that the Germans designated as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In doing so, these Jews were saved from deportation to Auschwitz.

Both Madritsch and Titsch took risks to protect Jewish laborers in the sewing plants that they operated in Kraków, Tarnów, and in the Plaszow camp. They were supposed to serve the German war effort and follow Nazi ideology. Instead, the men recruited other people, including a German policeman, and a German businessman. Madritsch was determined to negotiate with the German authorities and remain friendly with the notoriously brutal commandant of the Plaszow camp in order to move his plant to the camp and thus continue to save his workers. Madritsch and Tisch were outcasts who decided to go against the oppressive Nazi regime and rescue Jews.

In February 1964, Yad Vashem recognized Julius Madritsch and Raimund Titsch as Righteous Among the Nations. Madritsch wrote a text about his wartime activities and relayed them in a German-language interview in 1983.